The Wind Rises

(Kaze Tachinu):

Written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Starring: Hideaki Anno, Miori Takimoto,

Hidetoshi Nishijima, Masahiko Nishimura, Steve Alpert, Morio Kazama, Keiko

Takeshita, Mirai Shida, Jun Kunimura, Shinobu Otake, Nomura Mansai. Running

Time: 126 minutes. Based on the manga by the same name by Hayao Miyazaki

Rating: 4/4

**spoiler

warning- there’s a lot I want to say about this movie, and much of it will

require me to delve into the content of the entire film. Not that it’s really a “story movie” anyway,

but for those of you who avoid any spoilers on principle, here’s the fyi**

If you had taken a census of

Miyazaki’s most devoted fans, critics, and all-around cinephiles that have

followed his career over the years and asked them to opine on what they would

envision his last film to be like, The

Wind Rises would not be it.

Ironically, that makes it, in many respects, a quintessential Miyazaki

film, because what else has drawn us to his work over the decades, other than

the fact that his films are never quite what we thought they would be? Each one has been something refreshingly new,

often something at complete odds with what came before. In this aspect, The Wind Rises is no exception.

Whether or not it will have the staying power of his earlier works, and

whether or not there is more than in some of his other films to actively

criticize, remains to be seen.

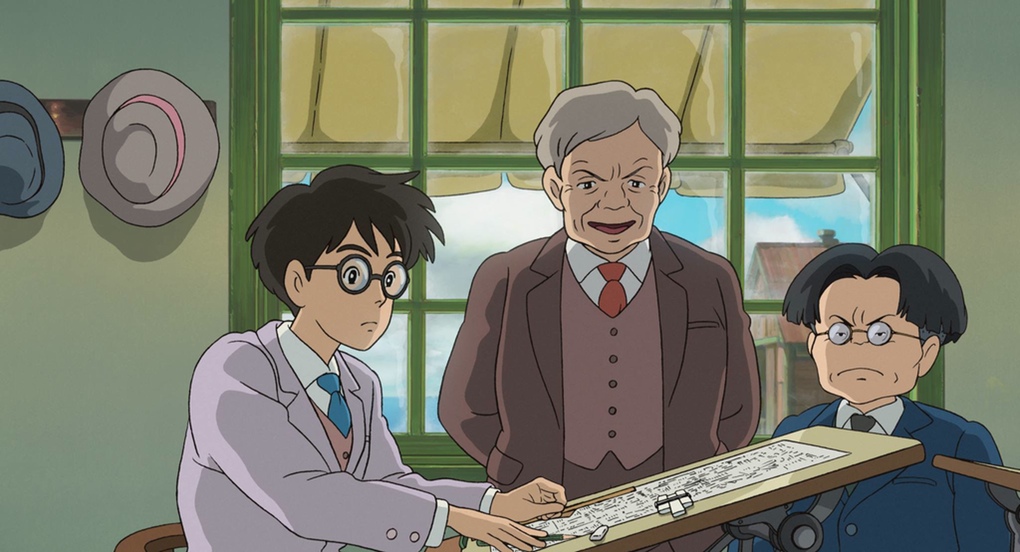

The

Wind Rises is a heavily fictionalized account of the early life of Jiro Horikoshi, the designer of the Zero fighter plane, a huge technological leap

forward for the Japanese air force during WWII that temporarily outstripped all

other planes in the world, and which were later made infamous by their use as

suicide vessels by kamikaze pilots towards the end of the war, often to

devastating and horrifying effect. When

the film opens, however, none of that dark future exists yet for Jiro. He freely dreams of a bright,

sunlight-and-color-filled sky, through which he flies his own imaginary plane

as the morning sun streams over the hills.

It’s the ultimate escapist fantasy, flying over house and field as the

people look up in wonder and awe. However,

even at that age, premonitions of a dark future start creeping in to his

consciousness- a massive zeppelin adorned with the Iron Cross looms suddenly

out of the clouds, armed to the teeth with bombs and muttering shadows that

will remind many of the night spirits in Princess

Mononoke. A large, undulating

torpedo strikes his craft, shattering it, and he falls.

It is a scene meant as a premonition

for what is to come. Since his own

eyesight is too poor for flight school, Jiro eagerly decides to pursue studies

as an engineer so that he too can one day design the planes he loves so

much. Beginning then and continuing throughout

his life, he is encouraged by the Italian aircraft designer Caproni. Or rather, by his imaginary version of

Caproni. Every so often, usually when

Jiro is at a low point in his life, Caproni visits him in his mind, the

“kingdom of their dreams,” as he puts it, where they straddle the wings of

planes in flight and ponder why they are driven to build machines that they

themselves will never use, especially machines utilized for war.

Later, on his way to the university

to pursue his higher studies, the train is stopped by what is now called the

Great Kanto Earthquake, which utterly devastated Tokyo in 1923. A shadowy wave approaches the coastline, and

the houses and ground rise and fall like bedsheets being shaken out in the

morning, while the Earth groans like some monstrous beast waking after

centuries of sleep. Trying to make sense

of the disaster after leaving the train, he stops to help the mother of Naoko,

a pretty young girl who happened to catch his hat earlier as the train sped

over a bridge. They will eventually be

reunited, at a mountain resort where they fall (rather quickly) in love, and

soon after marry, even though she is suffering from incurable

tuberculosis.

Before their reunion and marriage,

however, Jiro finishes his studies and begin work at Mitsubishi, which at that

time was feverishly churning out new airplane designs in the hopes of winning

much-desired government contracts for the military. For most of the rest of the movie, we follow

the various events and experiences that eventually inspire Jiro to create the

Zero. As his vision approaches reality,

however, Naoko grows sicker and sicker, eventually dying the same day as the

first test flight of Jiro’s plane. The

conjunction of these two moments (although said death is not depicted

on-screen, but rather heavily implied) seems to be a sharp and biting allegory

for what the birth of the Zero plane signified- its creation may have been

inspired, impressive, and technically ingenious, but it also heralded in an

even more deadly phase in the Sino-Chinese war, and would be responsible for an

immense amount of destruction and death in the wider World War just over the

horizon. As it touches down, the

technicians and military higher-ups exuberantly celebrating, a person of

beauty, innocence, and purity leaves the world forever. Jiro’s much longed-for convergence of dream

and reality brings in destruction on an unimaginable scale, and pushes out love

and joy. The war that has haunted Jiro

since his childhood has caught up to him at last.

There are two major themes in The Wind Rises that I felt to be of

paramount importance. One is, rather

obviously, wind itself, and all the forms that it can take. The title of the movie is taken from a line

in a poem by the French writer Paul Valery, called “The Graveyard By The Sea,”

and is recited several times by various characters; “The wind is rising. We must try to live.” And rise the wind does, in many forms and in

many ways, representing beauty, kindness, and gentleness, but also the

overwhelming tide of events in which an individual like Jiro, no matter how

well-intended or idealistic, can become utterly lost.

Sometimes, the wind pulls gently at

the grass in the field, accentuating the beauty of the natural world. Other times, it tears at the clothes and rips

an umbrella out of someone’s hand. The

wind both lifts up the airplanes of Jiro’s dreams and those of his reality, but

is also capable of ripping them apart at the seams, and does so quite

often. It can lead to beautiful moments,

like the wind that blows Jiro’s hat into Naoko’s hand, but like that selfsame

wind, it can also herald ruin, blowing the searing ash and embers from the

first fires started by the quake in every direction, causing whole swaths of

the city to be consumed in flame. The

wind is a force inexorable, far beyond any one person’s ability to contain,

much like the fate that envelops both Jiro and his country. And yet, as the original poem itself suggests,

even when faced with an overwhelming tide, we are still driven by a yearning to

go on, to continue even when it seems that all purpose in doing so is

lost.

The second major theme within the

film is that of dreams, and of where the lines between dream and reality can be

drawn. In several scenes, characters

refer to life as wondrous, something dreamlike at its best, and it is from such

a dreamlike state that Jiro seems to perceive much of that which happens to and

around him, as if he is permanently emotionally detached from the world. His sleeping and waking fantasies of flying,

both the wonderful and the terrible, are freely interspersed with his supposed

waking moments, to the extent that it’s often hard to tell them apart at

first. Conversation with fellow

engineers will suddenly shift to include images of the plane in flight, and

those present react as if they all were seeing the same image. Even the “real” parts of Jiro’s life come

across as dream-like; there are no clear transitions from one scene to the next,

and sometimes we only learn several minutes into a conversation that several

years have gone by. In this sense, the

film itself is much like a dream- a scene begins, and we have no idea how Jiro

got there, or when, and why- he is simply there, and we must observe what

transpires. Perhaps the entire film is a

dream, woven out of the fabric of Jiro’s first literal flight of fancy in the

very beginning.

That the technical side of the

movie- the quality of its animation and the effectiveness of Joe Hisaishi’s

soundtrack (not, perhaps, as memorable as his work in other Miyazaki classics,

but still fitting for the work’s tone)- is without reproach is beyond

question. Where I (and a great many other

critics) found fault in the film was more in the specifics of its story and

execution. I do not believe I can

overstate how much of a slow-burning film this is. I have stated previously that many of the scenes

transition with effectively no fanfare.

A great number of said scenes are dominated by technical talk concerning

the mechanics of aviation. This is not

to say that these scenes are bad- I found them fitting in the context of the

film- but I cannot blame anyone who finds the film so boring that they mentally

check out before the end (which I a shame, because I believe it’s in the last

act of the movie that the entire enterprise comes together).

Further criticism can be made of Jiro’s

relationship with Naoko, who, it becomes fairly clear, exists simply as an

object of beautiful and innocent perfection for Jiro to lose at the necessary

moment. This will be particularly

surprising for some, given the incredible roster of female characters (both

leads and supporting) that Miyazaki has provided us over the years. As stated above, I found her character and

their relationship as a whole to be more of a metaphor for the costs of

militant nationalism, but again, the implications that that is the intended

interpretation are small indeed, so like with the film’s length, I can

sympathize with those who found it to be something of a distraction (indeed, my

favorite aspects of the film were those that had nothing to do with

Naoko).

Neither of those factors, however,

has been nearly as great a source of division and controversy as the simple

fact that the overarching aim of the film is to portray Jiro in a sympathetic,

and in some respects flattering, light. At

this point, I must move away from the film to provide some needed historical

context for the piece. At the time that

Jiro was working at Mitsubishi and designing the Zero, Japan was not only in

the process of militarizing and brainwashing much of its citizenry in

preparation for war against the United States, it was already engaged in one of

the most brutal conflicts in history, its invasion of Korea and mainland

China. The atrocities committed by

Japanese forces, which I will not list here, are a point of contention between

Japan, China, Korea, and other Asian nations to this day, in large part due to

continued efforts by the Japanese government (and by a not-insignificant size

of Japan’s population as a whole) to either deny outright or simply ignore many

of the worst aspects of Japanese wartime policy. Although Jiro was not directly involved in

military policy or wartime operations, his Zero added its own dimension of

destruction and pain to the conflict, even before it became the suicidal

coffins for scores of young Japanese pilots.

What has inspired so much

controversy and passion is the fact that none of the above- the brutality

inflicted by the Japanese in China and other places, the militarizing of the

society, the repression of dissent and free speech- is directly shown or alluded

to in the film. Not that the war is

ignored. Jiro’s co-workers refer several

times to the winds of war everyone knew was coming. At the resort where Jiro and Naoko are

reunited, a German fleeing the Nazis compares the place they are all at to

Thomas Mann’s “Magic Mountain,” a place where anything painful or uncomfortable

can be forgotten; “The war in China?

Forgotten! The puppet government

in Manchuria? Forgotten!”

This lack of open, direct

acknowledgement of Jiro’s part in the war is, in the eyes of some, exacerbated

by the final scene of the movie; he is once again in his dream world with

Caproni, except now the ground is littered with the charred bones of his Zero,

all destroyed. After commenting to Caproni

that the world of his dreams has now become his own personal hell, he says

wistfully, “None of my planes returned.

Not one.”

For some critics, this is a callous

effort to further feed the Japanese tendency of simply not acknowledging the

suffering caused by the war outside of that which Japan itself

experienced. It can be argued that,

through the line, Jiro is expressing his sorrow over the pilots and their

victims AS WELL AS the planes, but again, that is very much open to

interpretation. Despite that aspect,

however, the rest of the film is clearly very anti-war in general. Both the film and its creator very much

embody this strange divide. Miyazaki

cannot be accused of ignorance when it comes to WWII- he has spoken openly of

Japanese wartime policy in the past, and has adamantly opposed Shinzo Abe’s

efforts to rewrite Japan’s strictly pacifistic post-war constitution. When interviewed about the film, he stated

quite firmly that the Japanese government acted out of “arrogance,” and sowed

the seeds of its own destruction. On the

other hand, he holds Jiro as blameless, as a visionary whose admittedly

impressive creation was twisted by others for dark uses. He says that his primary inspiration for the

film was a single line from Jiro’s memoirs, written long after the war’s end; “I

just wanted to make something beautiful.”

Miyazaki clearly takes Jiro at his

word. Others do not. Audiences and critics, both in Japan and

abroad, have been as starkly divided over the film and its subject matter as he

is. Some on the conservative end of the

spectrum have attacked the film for containing what veiled criticism of

Japanese wartime policy it does have, with a few even going so far as to label

Miyazaki “anti-Japanese.” Conversely,

many on the Japanese left, as well as in countries that suffered the most from Japanese

aggression and the abilities of the Zero plane in particular contend that

Miyazaki does not go far enough, that he ignores not only the horrors of

Japanese aggression in general, but also what aspects of said aggression can be

linked directly to Jiro’s life and work; another historical side unacknowledged

by the film is the fact that many of the Zero fighters produced during the war

were assembled by Korean laborers (read; slaves). One Korean-American critic, Inkoo Kang, wrote

the following in her response to the film; “The Wind Rises is just one film, but it echoes an entire

country’s obsession with misremembering a deeply painful and extraordinarily

violent past. Japan’s wartime victimhood is a convenient lie its citizens have

told themselves for decades. That the aging Miyazaki has misguidedly lent a

patina of wistful beauty to that lie is a shame. The Wind Rises ends the illustrious career of a treasured

visionary on a repellent, disgraceful note.”

Even the question of slave labor

during the war, however, is not ignored entirely. When lamenting to Caproni over how his planes

are being used, Caproni simply tells him to think of the pyramids, asking if he

thinks the world would be better without them.

The implication here seems to be

that even though the pyramids, which were also constructed with slave labor,

most definitely caused great suffering for many, the world would still be a

poorer place if they did not exist.

Whether or not the pyramids are comparable to fighter planes is, again,

open to debate.

By now, you are undoubtedly

wondering where I stand on all of this.

And to be honest…..I am not sure.

In fact, during the process of writing this review, I have openly

worried on more than one occasion that my deep and abiding love for Miyazaki’s

works makes me biased enough to overlook the questionable way he tackles

history, or whether or not his treatment of the film itself as something like a

dream, drenched in unspoken and vague metaphors, really works the way he wanted

it to. Even when you disagree with

Miyazaki’s basic assumption underlying the film, that Jiro himself is someone

to be admired for his technical genius and his fierce passion for the dream of flying,

his deep-seated belief in the ultimate beauty of human effort has never shone

through more clearly. In several scenes,

the parts of the planes being tested are seen being taken to the field cleared

for flight by oxen-drawn carts, led by the poorest of farmers. Human dreams so often exceed the reality in

which they are born, but there is nobility in the dreaming, even when it is

surrounded by chaos.

On the whole, though, there are

enough aspects of the film itself that, in my opinion, do not work as well as

they should, enough that I do not think that, on its own merits, the film is on

the same level as Princess Mononoke

or Spirited Away. While I personally do not feel that the film

is historically or culturally insensitive in how it treats its subject matter,

I cannot blame others for disagreeing. In

his (seemingly) final cinematic act, Miyazaki has given us what may or may not

be among his greatest works, but what is, I think, his deepest, most complex,

most mercurial, and most intimately personal creation out of everything he has

made. As a result, The Wind Rises shows us, perhaps, much more of his own personal and

cultural flaws, biases, and idiosyncrasies than we’ve seen before, including the

ones many find objectionable.

Where The Wind Rises DOES succeed in achieving greatness is in how its

very existence provokes questions far above just those limited to the story and

subject of the actual film. Spoken and

unspoken meditations on war, peace, love, innocence, and the divergence between

dreams and reality permeate each frame and are enough on their own to provoke

hours of deep discourse. But what it

also provokes are questions and uncertainties regarding the very nature of art

itself, and of the artists who take it upon themselves to create. When using real events as a baseboard, what

are the artist’s duties to the historical truth, if there even are any? Can we fairly criticize an artist for

focusing on some aspects of the story and ignoring others, regardless of their

reasons for doing so? And if we can,

where do we draw the line, and how do we tell when an artist has gone too far,

or not far enough? To what extent can we

say that someone is guilty by association, even if they only indirectly

contribute to a crime?

I do not know the answers to any of

these questions. I do not know yet if The Wind Rises really is one of

Miyazaki’s best works. I do not know if

it is so reprehensible in its avoidance of the dark side of Japanese wartime

history as to be considered his “worst” film, at least from a moralistic

perspective. What I do know is that I

was moved in ways I could not begin to put into words by the movie. Not in great emotions, but in small shifts in

my thinking. I know that I have thought

long, and hard, and deeply, far longer than I normally do before writing up a

review. I have read an uncounted number

of reviews and reactions to this movie while writing my own, far more than I

usually do. I have asked myself a lot of

questions, and have actively worried about my own biases and viewpoints

coloring my perception of Miyazaki’s more debatable decisions in the film, also

something I rarely give extensive thought to.

And is it not a blessing for us to

be presented with something that makes us question so deeply, that defines easy

generalizations and simple lessons? Is

it not a gift, to be challenged to reevaluate and redefine our individual

attitudes and approaches to art and objective truth, and the divergences

between the two? Even if, after

considering all this, one feels compelled to condemn the film for its flaws and

how it treats its subject matter, was it not wonderful to be able to assert so

clearly what one thinks and why? Hayao

Miyazaki has, once again, provocatively pushed the boundaries of our

perceptions of the kind of stories animation can tell. He has had his visions, and his dreams, like

Jiro. The hesitation and, in some cases,

anger and/or frustration that this last work has caused aside, I would like to

think his efforts to make those dreams a reality have been far more beneficial,

inspiring, and life-giving than the Zero ended up being. He has let his mind soar on the back of the

rising wind. He has lived.

And now it’s our turn.

-Noah

Franc

This was a real treat to read. Reading it made me realize how much I missed the first time. I remember the dream sequences vividly--in fact, they probably were the stand-out for me. But much of the rest is a blur--which I freely blame on the EXTREMELY DISTRACTING English dub. I'm convinced it distracted me enough to take me out of the film.

ReplyDeleteIn any case, I did really appreciate the tension of creative beauty and creative destruction. I never felt that Mitazaki was downplaying the destructiveness of technology--it hangs over the film like a pall.

Whe I go back and watch it, I want to see if the romance works better for me--I was disappointed with it the first time, especially because I've seen more satisfying relationships in his previous films (Ashitaka and San in Princess Mononoke, Sheeta and Pazu in Castle in the Sky, hell, even Sosuke and Ponyo!) But when I go back I want to keep in mind what you said about this being a dream of sorts.

Anyway, I'm rambling. Great job, as always, and keep watching and thinking!

One of the reviews I read said that any dubbing of the film would be a crime. I need to see it again in Japanese too.

ReplyDeleteWhat did you think of the historical context? Ingoo Kang's comment really stuck with me after I read her article.